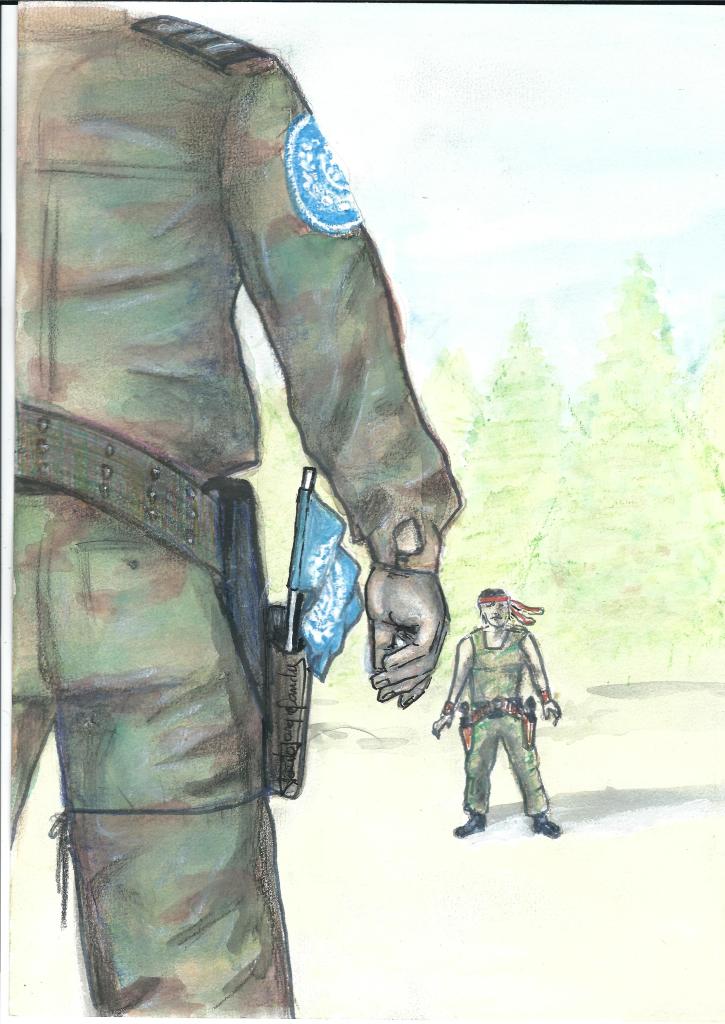

1 – Dress, think, talk, act and behave in a manner befitting the dignity of a disciplined, caring, considerate, mature, respected and trusted soldier, displaying the highest integrity and impartiality. Have pride in your position as a peace-keeper and do not abuse or misuse your authority.

2 – Respect the law of the land of the host country, their local culture, traditions, customs and practices.

3 – Treat the inhabitants of the host country with respect, courtesy and consideration. You are there as a guest to help them and in so doing will be welcomed with admiration. Neither solicit or accept any material reward, honor or gift.

4 – Do not indulge in immoral acts of sexual, physical or psychological abuse or exploitation of the local population or United Nations staff, especially women and children.

5 – Respect and regard the human rights of all. Support and aid the infirm, sick and weak. Do not act in revenge or with malice, in particular when dealing with prisoners, detainees or people in your custody.

6 – Properly care for and account for all United Nations money, vehicles, equipment and property assigned to you and do not trade or barter with them to seek personal benefits.

7 – Show military courtesy and pay appropriate compliments to all members of the mission, including other United Nations contingents regardless of their creed, gender, rank or origin.

8 – Show respect for and promote the environment, including the flora and fauna, of the host country.

9 – Do not engage in excessive consumption of alcohol or any consumption or trafficking of drugs.

10 – Exercise the utmost discretion in handling confidential information and matters of official business which can put lives into danger or soil the image of the United Nations.