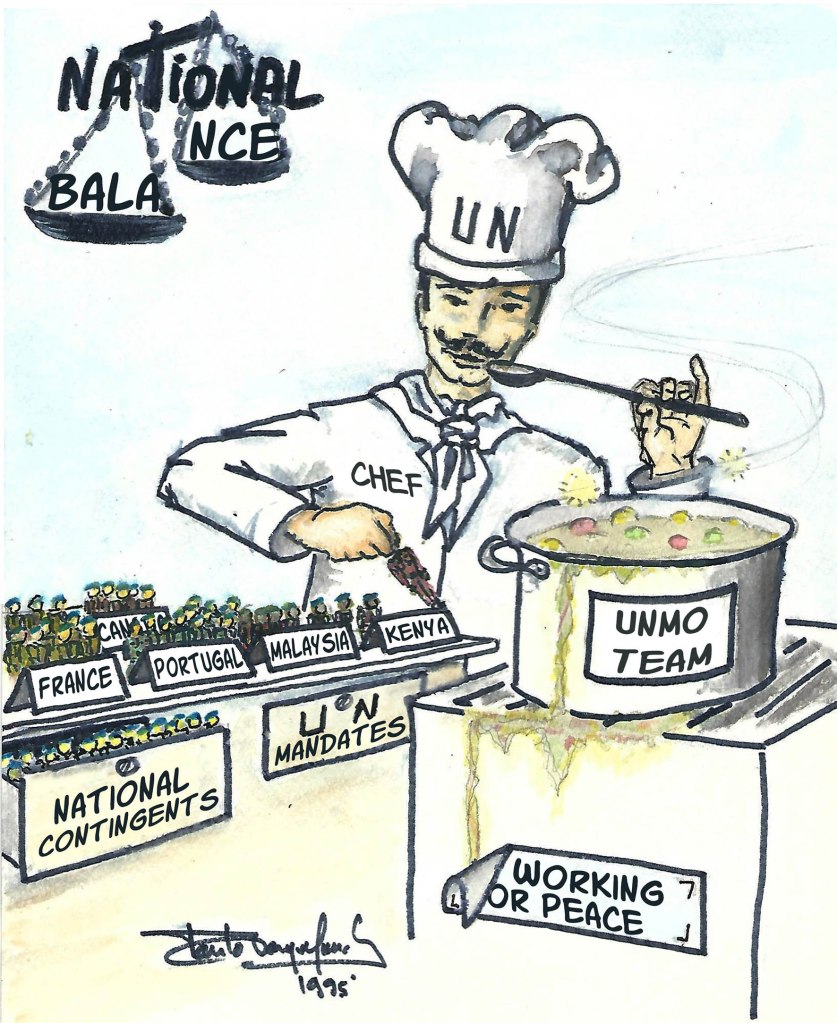

72 years ago, on the 29th May 1948, the United Nations Security Council approved the deployment of a Group of Military Observers (UNMO) to Middle East, tasked to observe and maintain the ceasefire during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. In 2003, the UN General Assembly decided that this date (29 May) should be considered the “International Day of the United Nations Peacekeepers”.

Há 72 anos, no dia 29 de maio de 1948, o Conselho de Segurança da Nações Unidas decretou o estabelecimento de uma missão de Observadores Militares (UNMO) no Médio- Oriente, com o objectivo de monitorizar e zelar pelo cessar-fogo Israelo-Árabe. Em 2003, a Assembleia Geral da ONU decidiu que esse dia (29 de maio) deveria passar a ser considerado o “Dia Internacional dos Capacetes Azuis”.

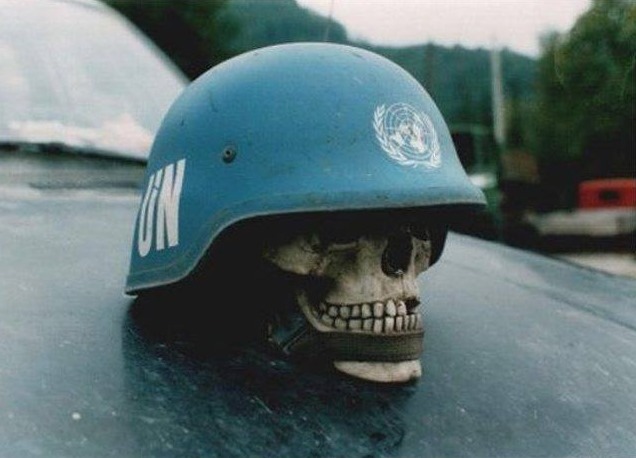

Since 1942, over one Million men and women have served as UN Peacekeepers. About 95.000 are still serving the UN in 13 field missions around the World. More than 3900 have died in the line of these noble duties.

Desde 1942, mais de um Milhão de homens e mulheres serviram as Nações Unidas como Capacetes Azuis. Cerca de 95.000 cumprem nos dias de hoje tarefas de Manutenção de Paz em 13 missões da ONU. Mais de 3900 Capacetes Azuis morreram no cumprimento da sua nobre missão.

Today, I honor all those who’ve died and praise those who’ve lived wearing a blue beret. Military, police and civilian staff alike; they all deserve my deep deepest respect.

Hoje eu honro aqueles que morreram e louvo os que estão vivos usando a boina azul. Militares, polícias e civis, todos merecem a minha mais sincera consideração.

Monumento aos mortos da Liga dos Combatentes no Seixal – Portugal – 29Maio2020

Thank you for your sacrifice!

Obrigado pelo vosso sacrifício!