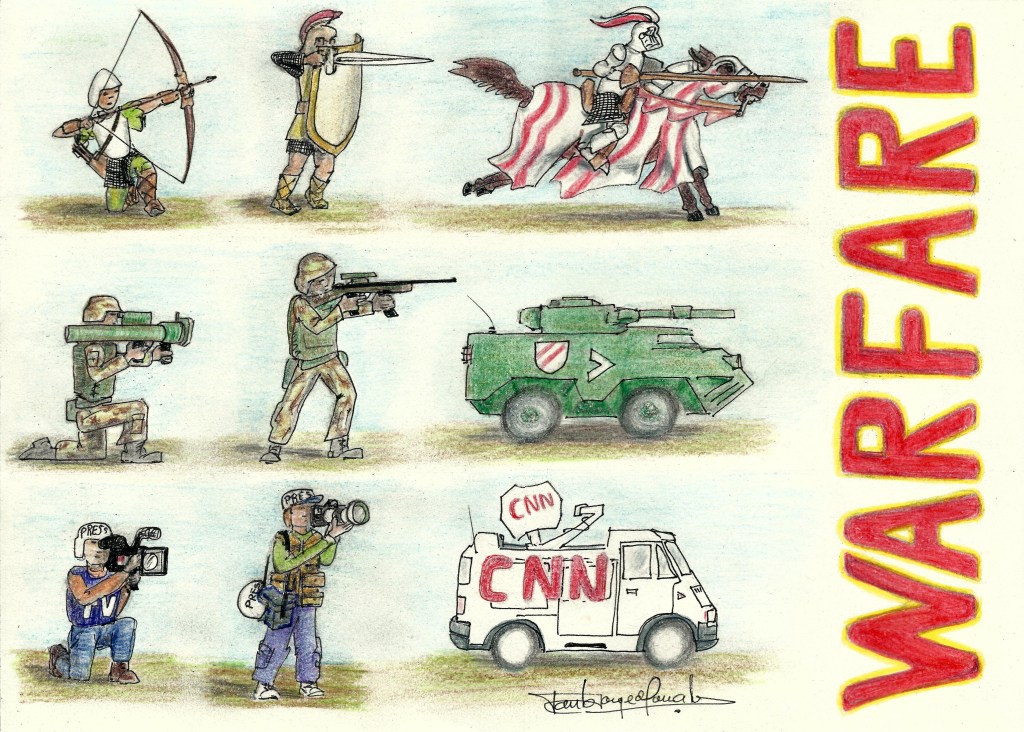

Numa certa madrugada gelada de 1995, após chegar ao Aeroporto de Pleso, em Zagreb – Croácia – a fim de embarcar no meu voo inaugural para Sarajevo, deparei-me com uma fila de capacetes azuis junto à cancela que dava acesso directo para a placa dos aviões. Juntei-me ao grupo dos camaradas da UNPROFOR e verifiquei que era ali mesmo, no exterior, que se fazia o check-in e embarque. Nada de luxo de terminais resguardados da neve com ar condicionado. Junto à cancela, recolhida numa guarita com o logotipo da ONU, estava uma mulher polícia da CIVPOL – a Unidade de Polícia Civil das Nações Unidas. Olhando para além da cancela podia-se ver um velho avião Antonov, sozinho no meio da placa meio nevada. Aquele teimoso veterano dos ares contrariava o seu aspecto museológico com as imensas horas de voo marcadas com manchas de óleo e fuligem na pintura (quase) branca da ONU. Na empenagem vertical da cauda, assim como na fuselagem, exibia orgulhosamente grandes letras negras a dizer UN, mostrando ao Mundo que se tinha fartado de “Guerra Fria” e agora era um “Guardião da Paz” (Peacekeeper).

Debruçada sobre a janela da sua guarita, a mulher polícia ia verificando as “guias de marcha” dos futuros passageiros, certificando-se que estavam na sua lista de embarque.

– “Bem-vindos às “Linhas Aéreas do Talvez” (Maybe Airlines) – Disse a polícia – “Acabei de ver passar a tripulação; a meteorologia não está francamente má; e ninguém está a disparar sobre os aviões em Sarajevo … desta forma “Talvez” vocês voem hoje”.

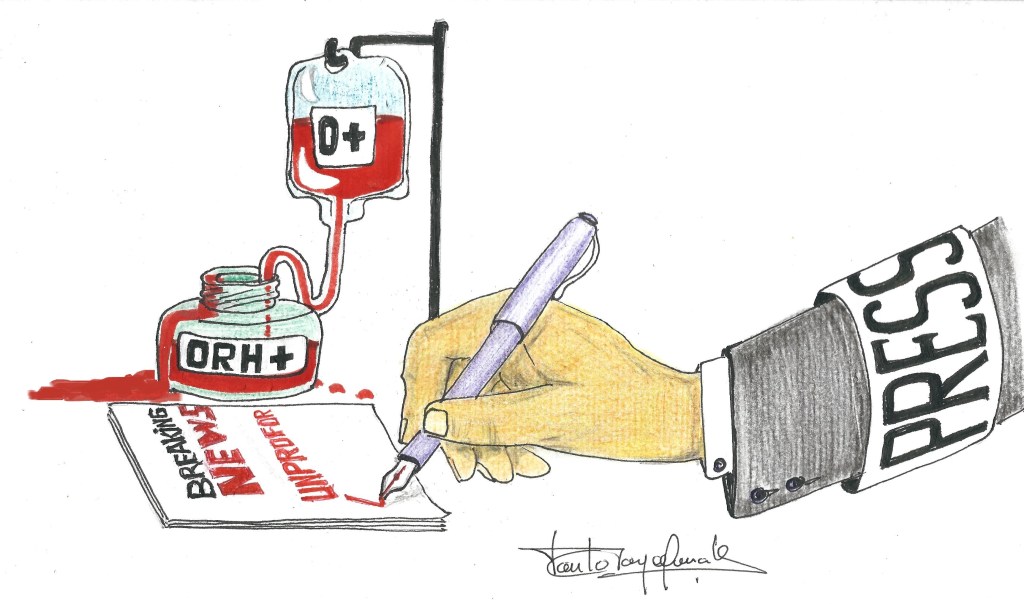

A alcunha (carinhosa) de Maybe Airlines devia-se ao facto de nunca se saber se havia voo ou não, se o voo ia chegar a horas ou não, ou mesmo se o destino era o inicialmente previsto ou não. Regra geral, não era um problema de falta de tripulações, ou mesmo de aeronaves; era, isso sim, um conjunto de situações que quase sempre tinham uma implicação negativa no planeamento da actividade aérea. Porém, não se pense que o pessoal da UNPROFOR estava desgostoso com as suas Maybe Airlines, pelo contrário, havia mesmo certo orgulho em voar naquela já afamada transportadora aérea. Havia até um carimbo disponível para carimbar guias de marcha e passaportes dos passageiros que o desejassem … e a maior parte deles faziam questão em ter esse carimbo nos seus documentos de viagem; tanto os militares como os civis.

Carimbo das Maybe Airlines num Passaporte (foto de Fernando Costa)

Entretanto, em Pleso, a mulher polícia levantou a cancela e gritou a plenos pulmões:

– “Passageiros para Sarajevo! Por favor dirijam-se à aeronave, mostrem o vosso cartão de identificação UNPROFOR à tripulação e embarquem. Deixem ficar aqui as vossas bagagens devidamente identificadas, porque seguiram num atrelado para o avião.”

Enquanto caminhava para o Antonov ia estudando o antigo Soviete, questionando-me se seria boa ideia ir para o ar dentro “daquilo”. A minha expressão deve de ter sido tão esclarecedora, que o tripulante responsável pelo porão de carga (load master) adivinhou os meus pensamentos e disse-me:

– “Meu amigo, bem-vindo às Linhas Aéreas do Talvez” vamos descolar dentro em breve e … TALVEZ cheguemos a Sarajevo; deseja vir connosco?”

Já sentados nos bancos de lona, e no meio de todos os ruídos e barulhos característicos de uma aeronave vintage, o load master voltou a falar (aos gritos):

– “Senhores e senhoras, este voo será “Não Fumadores”, porque as caixas à vossa frente são munições; … certifiquem-se que se sentam em cima dos vossos coletes à prova-de-bala e apertem os cintos; … tenham um bom voo!”

A rampa traseira fechou-se e lá fomos nós.

Embora o destino “mais sexi” das Maybe Airlines fosse Sarajevo, eles também voavam para Tuzla (na Bósnia), para Split (na Croácia) e para Belgrado (na Jugoslávia). Anos mais tarde o “franchising” de Maybe Airlines passou a aplicar-se a todas as missões da ONU que tivessem uma componente aérea. Contudo, independentemente do local e situação que voasse nessas aeronaves, nunca mais me esqueci do velho Antonov, que se recusava a ir para o Museu e continuava a voar na Bósnia Herzegovina.