Back in the UN mission in Angola 1992, every late afternoon Luena’s Regional Electoral Commission would express their needs for support flight for the following day. Those meetings were not exactly peaceful get-togethers, because it was not easy to accommodate the ambitious list of flight destinations requests with the shortage of UN aircraft in the Province of Moxico’s Capital – Luena.

The UN goal was to support the Angolan electoral process with airlift capability, but there were still ongoing armed skirmishes and firefights between the two major opposing political parties (MPLA and UNITA) in the premises of Town, and any technical refusal for flight availability by the UN representatives would be immediately considered “favoring the opposite force”. When we finally managed to have consensus about the next day air activity, it was time for another type of headache – the passenger and cargo lists. Regardless the type of aircraft, or the distance to be flown, the amount of people and cargo to fit inside was always huge.

For each distance there was the need of a certain amount of Jet A1 fuel. The further way the destiny was, the more fuel required on departure; the less people and cargo on board. We kept saying:

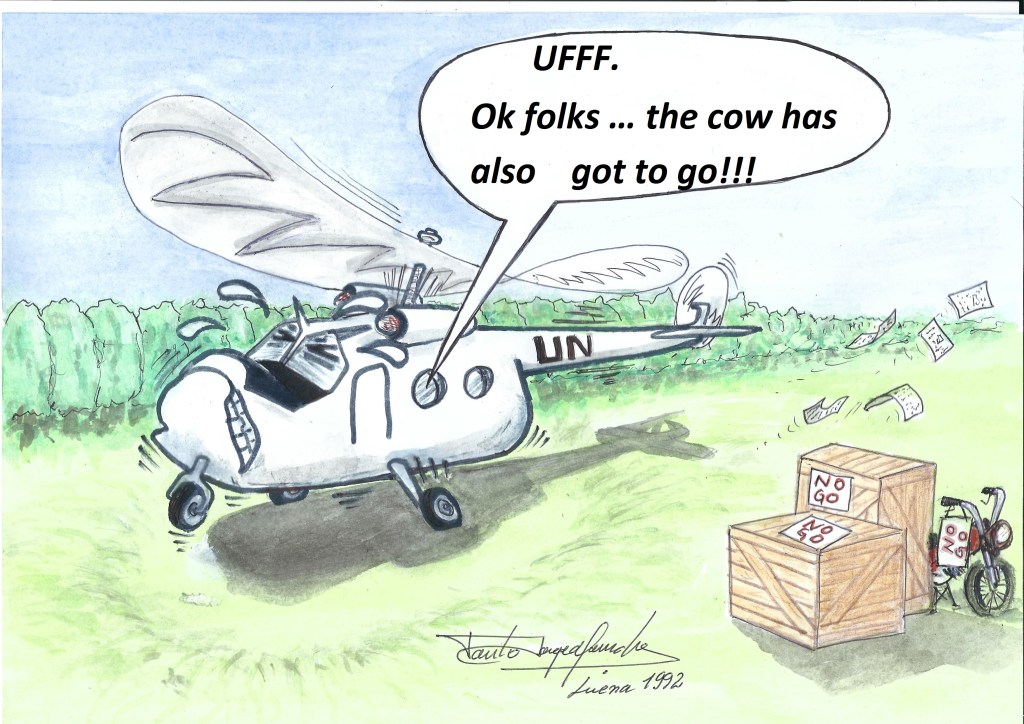

–“Gentlemen, for short flights, the MI-17 helicopter can only carry 22 passengers or 4500 kilos of cargo. You put more cargo, or more distance … we take people out!”

But that was not an equation easy to be understood by the Electoral Commission, which was focus on the elections’ date and wasn’t concerned with aeronautical technicalities. In result, the more the UN aviators restricted the take-off weight, the less the provided boarding lists were accurate. Rarely the amount of people at the helicopter’s door was the same in number or identification of the boarding list, and the cargo weight information was … a joke!

Boxes with electoral material with an estimated weight of 50 kilos, actually weighted 90 or more kilos; and the hand luggage concept was yet another problem … “instead of bringing an egg, they brought the chicken”.

The only solution was to feel how the helicopter would react to a “Guesstimated” maximum cargo take-off. The pilot would make small essays to take off vertically, and would decide, at the spot, how much stuff would have to go out, to gain airlift.

Hilarious now… scary back then!

Sometimes we had to fly more twice to the same destination, with the obvious negative impact on the amount of fuel available to the next day’s flight activity; but at the end, the entire mission was a major success.