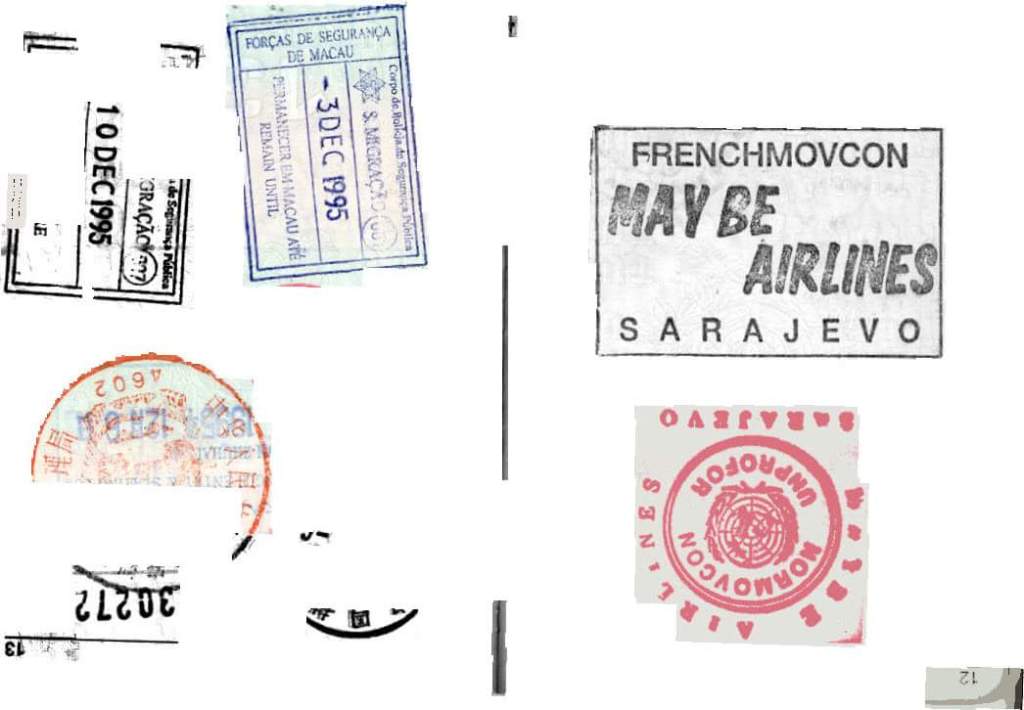

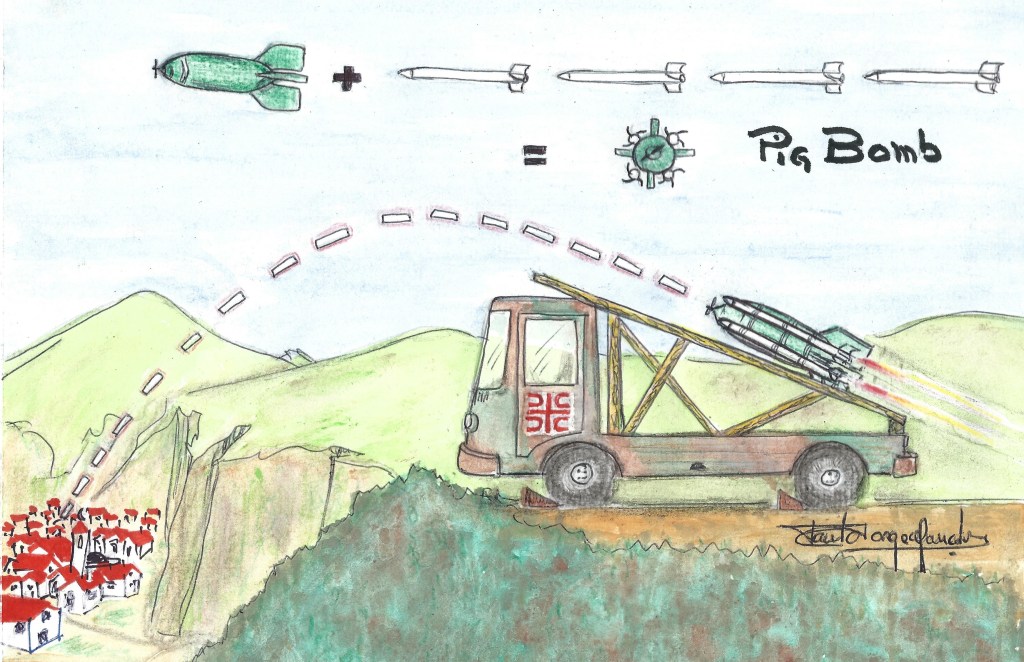

During the Bosnian conflict (1992/95), Sarajevo was a besieged City, with Serbian forces (VRS) dominating al the surrounding hill tops around the City. All but one: – Mount Igman. Like all other hilltops, Mount Igman had also been under Serb domination, but during the conflict it changed hands to become a Muslin (ABiH) stronghold. The problem was that, between the Town and Mount Higman’s foothill, there was a vast open land where Sarajevo Airport was. Crossing the runways meant being shot down by Serb snipers/artillery; therefore, the City remained besieged. Whenever the Serbs wished to close the Airport, it would be close; to both land and air transportation. The only way Muslins could go through the Airport … was under it! Therefore, they built a narrow tunnel, starting on the basement of one of the apartment blocks neighboring the Airport; going under the runway; and ending on the Muslin controlled area on the other site of the Airport, at Mount Igman’s foothill.

With the construction of that tunnel the Serbian siege to the City had a flaw, from which the Muslins could bring weapons and first need provisions, as well as transfer people in and out of the City. In 1995 everybody knew about the existence of the tunnel, but only a few actually knew where the access points were. The ABiH concealed that information from most people, in order to avoid the VRS heavy artillery to bomb its entry/exit.

Drilling the tunnel was not an easy enterprise, especially if it had to be handmade and in a concealed manner. However, its maintenance was no less hard. The terrains above were not stable, and the constant movement of aircraft was an added problem. In more than one occasion, several portions the tunnel collapsed while people were using it. Reconstruction works were a permanently ongoing, many times fighting with inundations and loose soils. Furthermore, the tunnel was quite long, without air extraction or any time of injection of fresh air, it was customary for people to have serious respiratory problems while crossing it.

The construction, maintenance and use of Sarajevo’s Tunnel are intrinsically a part of the City’s recent history, a demonstration of its population struggle for survival. Years later, after the war ended, the tunnel collapse definitively, but a small part of it became a Sarajevo touristic attraction.