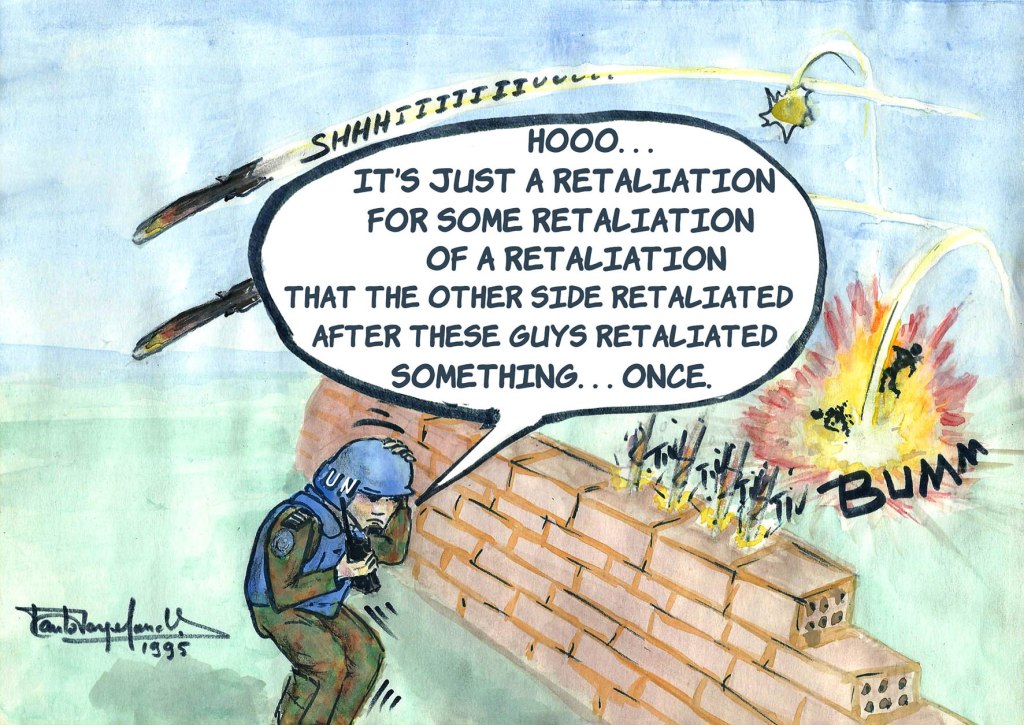

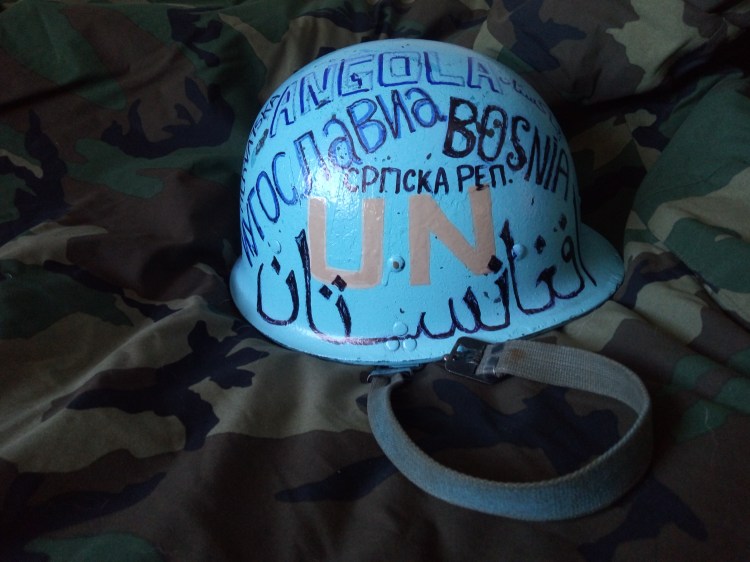

Up until about 2008, the wars also had a Forward Line of Own Troops (FLOT) in our living rooms, more specifically – in from of the TV set. It was common to hear the buzzwords “if you control the media contents, you have access to the hearts and brains of your audiences”. The military did it; politicians did it; even religious entities and large commercial enterprises did it; everybody did it.

Hence, in order to gain “media supremacy” over the enemy, there was a specific kind of battle going on. Much like in the conventional maneuvers, the military had specific units tailored to deal with the media representatives; they had coordinated activities to show/hide whatever the forces were doing, etc.

“Why are you using the past tense?” – You may ask. Because, just when everything was getting in perfect sync, and the greater military power also had the upper hand in dealing with the media; mobile devices were introduced on the battle field, and the news media jumped from the living room to our coat pocket. The “24 hours news media report” became the “86.400 seconds news feed”, and everybody is a journalist.

Soldiers were live-streaming their own death in Afghanistan’s battle fields. Forget the “CNN effect”, we are seeing now the War reality show in the palm of our hands … without much censorship; or so we think!

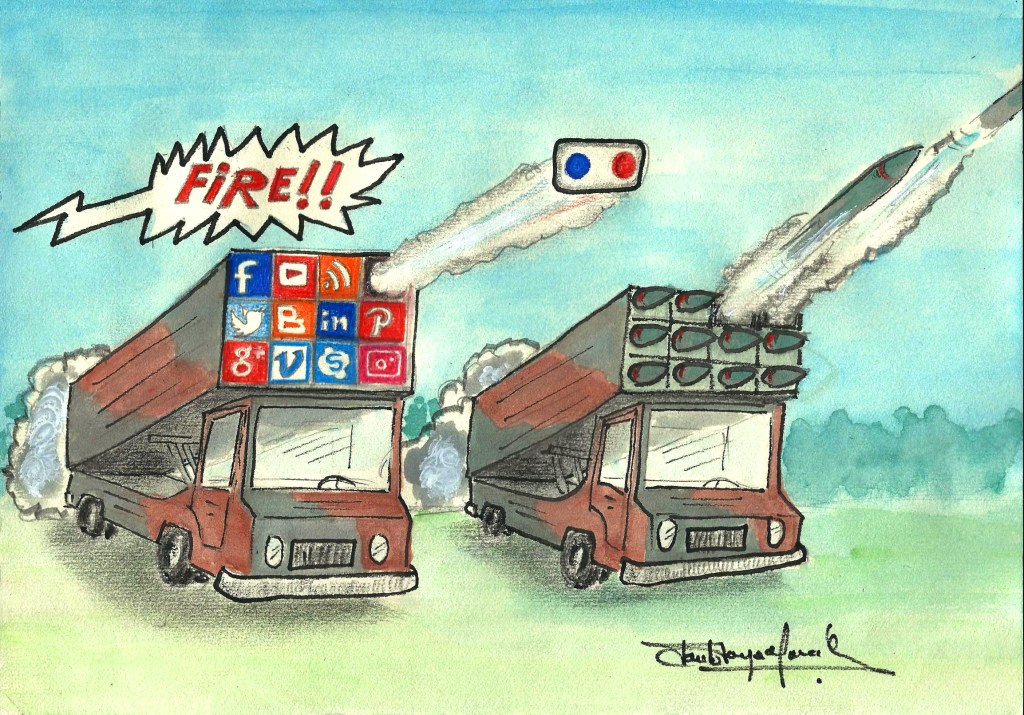

“If you can’t beat them, join them!” therefore, the military decided to jump into the cyber news media environment.

Battles are now fought not only with kinetic weaponry, but also (probably with priority) with social networking tools and concerns.

“Concerns?” – yes concerns, because, sometimes “we want to see without been seen”, others “we want to see as much as been seen”; and that requires new a doctrine, and a new approach to the issue.

The new battlefield non-lethal actions, either being Public Information or Psychological Operations, are all part of Strategic Communication Campaign, which, undoubtedly will be using social media networks to achieve the same goal: Information supremacy at the home FLOT; reaching where no “paper bullet” has reached before!