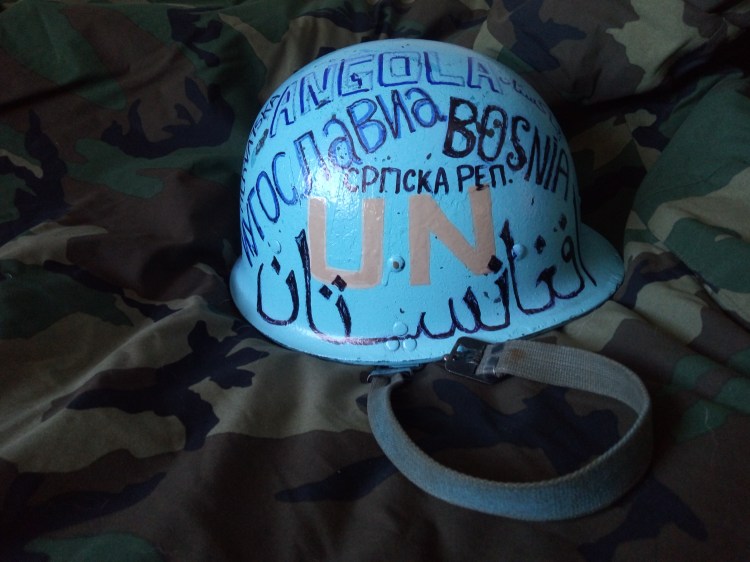

The violent cessation of Yugoslavia brought to the discussion forums concerned with “crisis resolution” some lessons that, apparently, we insist on not learning.

Economic difficulties generate social dissatisfaction, which leads to the emergence of rowdy leaders, with fiery speeches, which open space for the confrontation between the institutional power and popular masses.

This is true both in developed countries and in those considered to be in the so-called third world category. If the social conflict is supported by nationalist or ethnic-tribal differences, everything becomes far more complicated. Any student of the subject knows that it is much more painful and expensive to engage in the remediation of a regional conflict than it is in the timely commitment to resolve a localized dispute at the start.

The Yugoslav conflicts (1992-1995) should have taught us that:

– If not solve at the start, internal conflicts tend to move quickly into serious problems, with international consequences (migration, importation of the same problems within the borders of the hospitable country), difficult to handle latter in the developing process;

– The political, humanitarian and/or military response to such crisis must be fast, flexible and coordinated / cooperative, with the capacity to deploy and remain in the intervened territories for long periods of time. Organizations with strong logistic supplier branches (such as the military), become a major player in such theaters;

– The course of action in a “Coalition” mode, where several countries come together to resolve a crisis, should be encouraged involving as many countries as possible;

– The five countries with a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (China, , France, the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Russia) will have to commit not to halt the resolution process and to sponsor an international mandate (with proper Rules of Engagement) empowering the Coalition forces on the ground to act accordingly;

– Regional international institutions (OSCE, NATO, EU, AU, etc.) should strive to resolve the conflicts in their respective areas of influence;

– The resolution of problems at the place of origin avoids the spillover of those problems beyond the intervention borders.

“If we don’t go to their place and help them, their problems will end up at our doorstep, endangering us!”

However, it will never be too much to remember that “Humanitarian Aid” is a poor substitute of “Human Rights”. Humanitarian Aid is a fieldwork, done by people dedicated to supporting and assisting the most needed, in a selfless and neutral way. It should not be confused with the political activity required for the implementation of Human Rights, which requires (not neutrality) impartial and robust decision-making, in order to implement the internationally accepted rules of Human Rights and the necessary “call to responsibility” of those who violate it.

In this last aspect, there’s another registered (but little learned) lesson: -The absence of Humanitarian Aid causes conflicts, but when it is distributed in a less rigorous way, it tends to prolong armed conflicts; because it often ends up in the wrong hands, increasing exponentially all sort of illicit profits and interests in continuing the conflict.